Introduction: The Hidden Blueprint of Power

Why do some workplaces, political movements, or social groups become tense, unhealthy, or even harmful, while others encourage people to grow? This question has shaped much of my personal and professional observation. Over time, I’ve noticed that the answer often isn’t as simple as identifying “good leaders” and “bad leaders.” Instead, leadership tends to unfold along a predictable spectrum that can be seen in nearly every environment—corporate, civic, religious, or social.

This article explores those patterns by examining leadership styles, cultural narratives, communication habits, and subtle indicators of dehumanization, we can begin to understand why groups become unhealthy and what supports healthier, more empowering environments.

My goal is to offer a framework based on experience, research, and the perspectives of psychology, social science, and organizational theory.

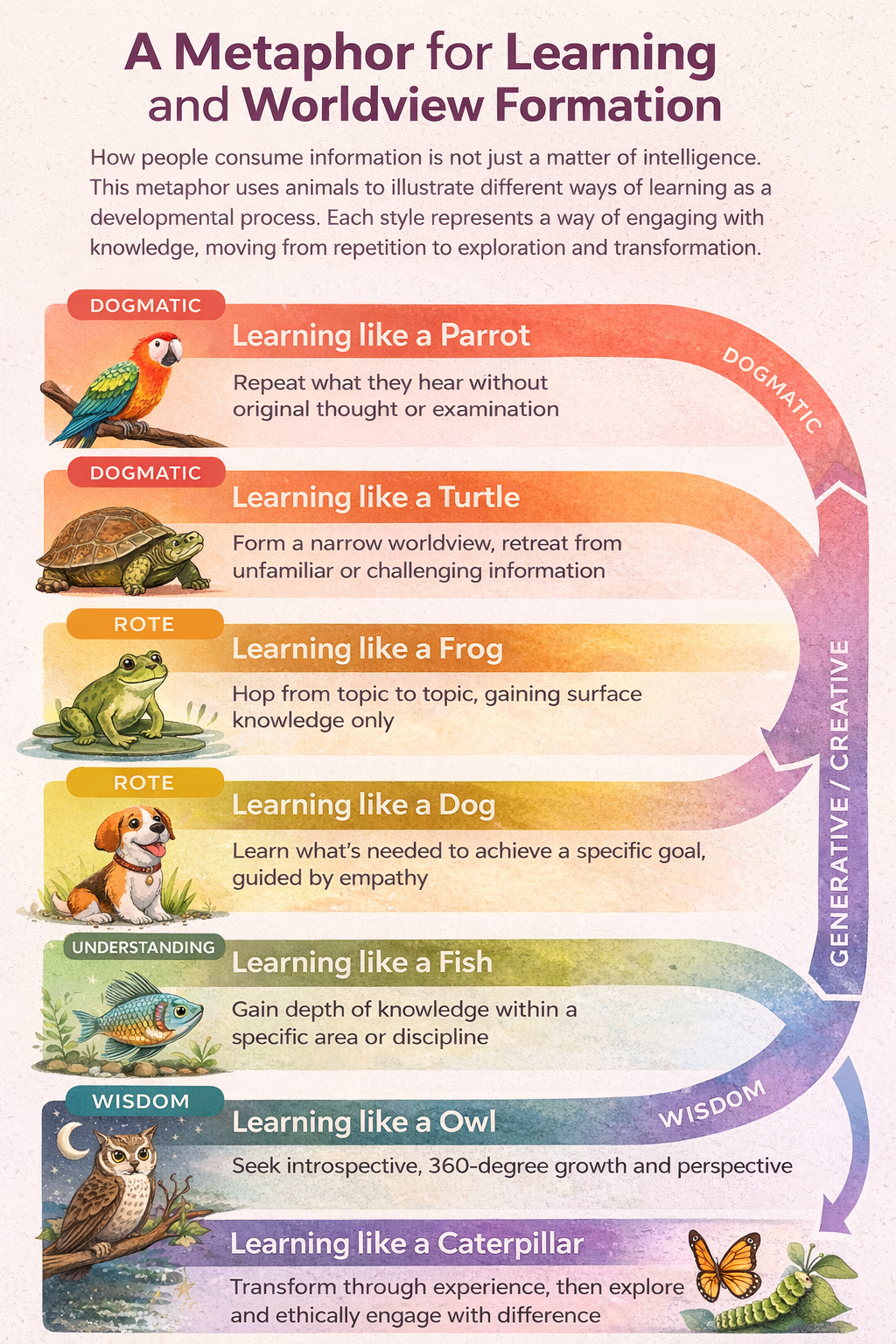

Takeaway 1: Leadership Isn’t a Title—It’s a Spectrum One of the most useful observations is that leadership is not a fixed trait or job description. Instead, it exists on a continuum of behaviors ranging from destructive to deeply empowering. This spectrum can help make sense of the wide variety of leadership styles we encounter, especially when titles alone do not reflect actual behavior. A practical version of this continuum includes six archetypes:

- Demagogic Leader

- Manipulative Transactional Leader

- Neutral/Conventional Transactional Leader

- Guiding Leader

- Hero (Interpersonal Moral Courage)

- Transformational Leader

Each reflects a different way of influencing others. The demagogue uses fear, identity, and manipulation. Transactional leadership relies on authority, rules, and incentives. Guiding leadership emphasizes support and connection. Heroic leadership shows interpersonal moral courage. Transformational leadership inspires collective change through a shared vision.

When viewed as a progression, the spectrum shows how influence evolves—from coercive forms of power to more relational and value-driven forms.

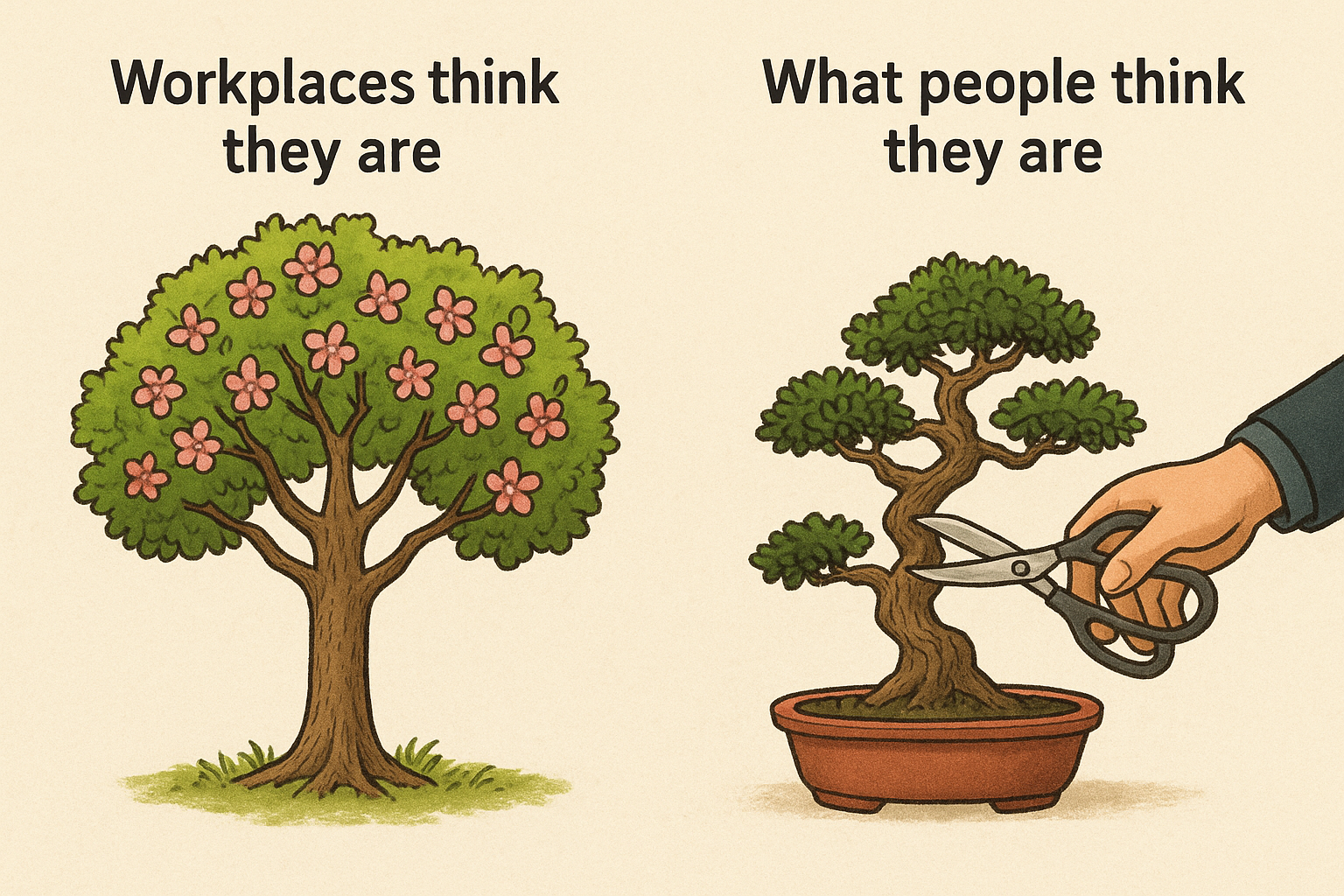

Takeaway 2: Workplaces Can Exhibit “Cult-Like” Dynamics While the word cult is often associated with extreme religious or political groups, the underlying dynamics—control, pressure, and isolation—can appear in more ordinary settings, including workplaces. This observation isn’t meant to sensationalize but to highlight common behavioral patterns that can be measured and recognized. Some key indicators include:

- Information Control – A single dominant narrative that cannot be questioned

- Conformity Pressure – Subtle or overt pressure to avoid disagreement

- Insularity – “Us vs. them” framing that isolates members from outside perspectives

These tendencies can emerge under many leadership styles, but they often correlate with leaders who rely heavily on authority, fear, or rigid control. Conversely, leaders who encourage questioning, openness, and shared accountability reduce these patterns. This framework is helpful because it focuses on observable behaviors rather than labels or intentions.

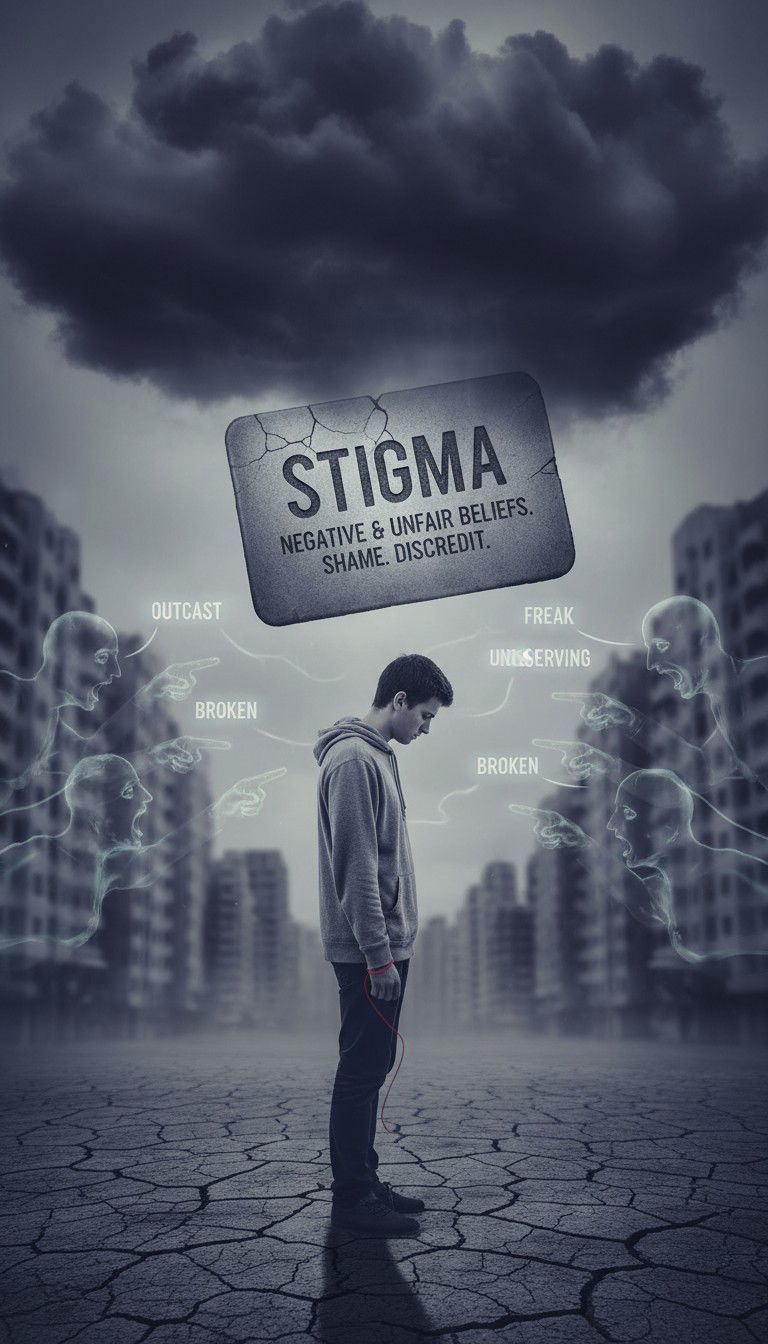

Takeaway 3: Dehumanization Is a Slow Progression, Not a Single Act

Destructive behavior rarely begins with overt harm. Instead, it moves gradually through a series of small steps. This progression is well-documented in psychology, including Philip Zimbardo’s insights from The Lucifer Effect. The Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated how quickly dehumanization can escalate once individuals are reduced to roles, labels, or numbers. Three meaningful stages include:

- Objectification – Seeing people as “resources,” “problems,” or “units”

- Psychological Violence – Gaslighting, shaming, intimidation, or humiliation

- Ideological Dehumanization – Framing a group as inferior or dangerous

Even minor ethical lapses contribute to this progression. When disrespect becomes normalized, empathy erodes, and harmful behavior becomes easier to justify. Recognizing the early stages creates opportunities for prevention long before an environment becomes overtly toxic.

Takeaway 4: Rethinking the “Hero” as a Protector of Dignity

The term “hero” is often reserved for large-scale transformation or extraordinary acts. In this framework, however, heroism is far more personal and accessible. A hero is someone who protects another person’s dignity even when there is social risk. This definition emphasizes:

- Small actions over grand gestures

- Individual protection rather than system change

- Moral courage instead of authority or status

Examples include speaking up against harmful language, supporting someone who has been dismissed or gaslit, or offering solidarity to a person who is being excluded. This reframes heroism as something anyone can practice, regardless of role or title.

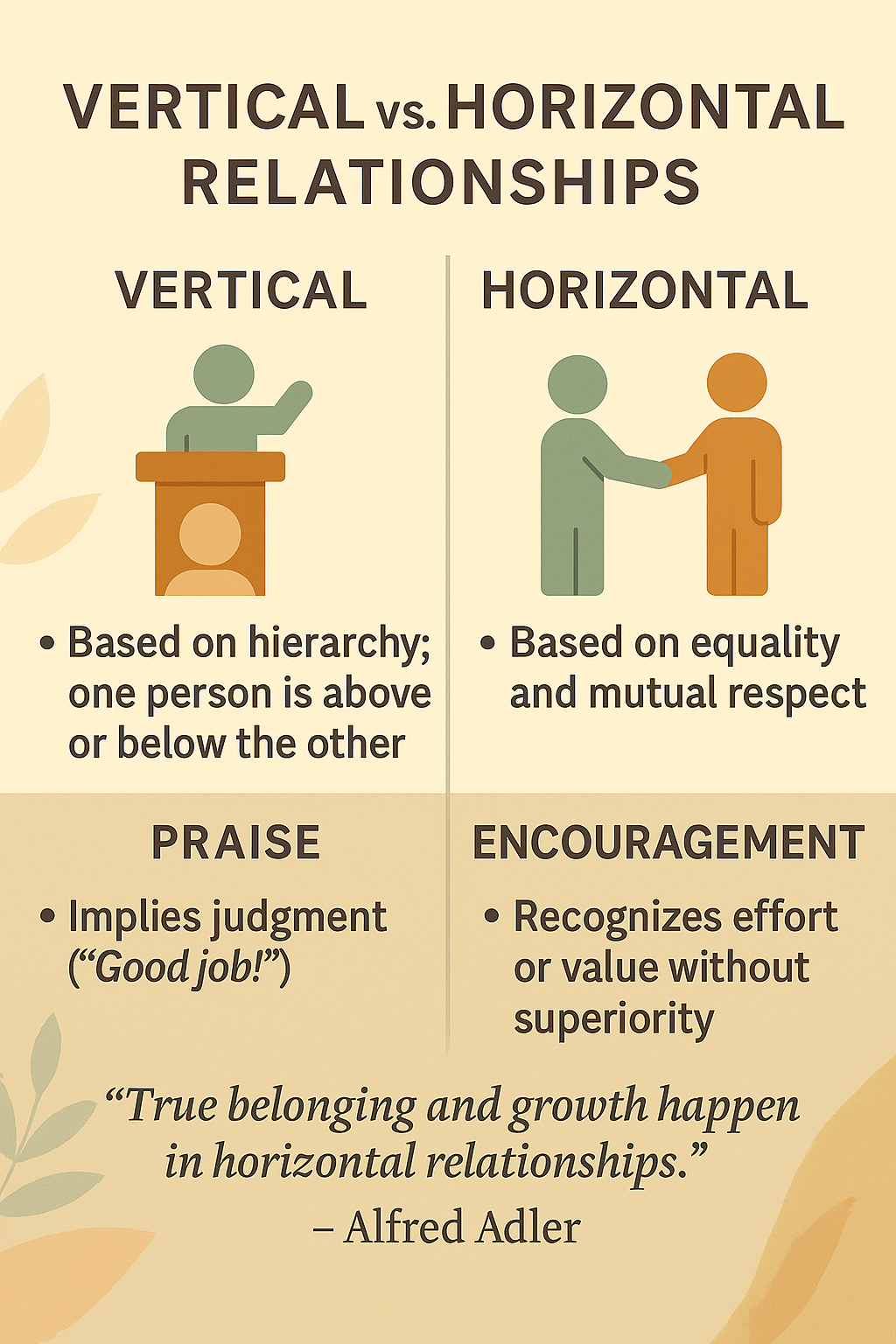

Takeaway 5: Communication Style Reveals Inner Leadership Beliefs Communication isn’t just a technique—it reflects underlying beliefs about power, hierarchy, and dignity. Drawing on Edgar Schein’s work, communication can be viewed along a spectrum:

| Communication Style | Associated Leadership Type |

| Domination / Commanding | Destructive / Transactional |

| Humble Inquiry / Intimacy | Guiding / Heroic / Transformational |

As communication shifts from commanding (“telling”) to inquiring (“asking to understand”), the leader’s ego decreases and space for dignity increases. This shift supports psychological safety and healthier group dynamics. It also aligns closely with leadership models that emphasize humility, curiosity, and shared agency.

Conclusion: Understanding to Action

The patterns described here—leadership types, cultural narratives, communication styles, and the progression of dehumanization—are not abstract theories. They are observable, repeatable, and relevant to everyday experiences in workplaces, families, communities, and political environments.

Understanding these patterns allows us to recognize early warning signs and choose more constructive responses. It also helps us appreciate where healthier leadership already exists and how it can be strengthened.

If there is a final takeaway, it may be this: meaningful change often begins with small acts. A single moment of moral courage, a shift toward dignified communication, or a decision to ask questions rather than make assumptions can interrupt harmful patterns before they escalate.

What is one small, dignifying act you can take this week to support a healthier environment around you?