Workplace Safety: From Profession to Industry

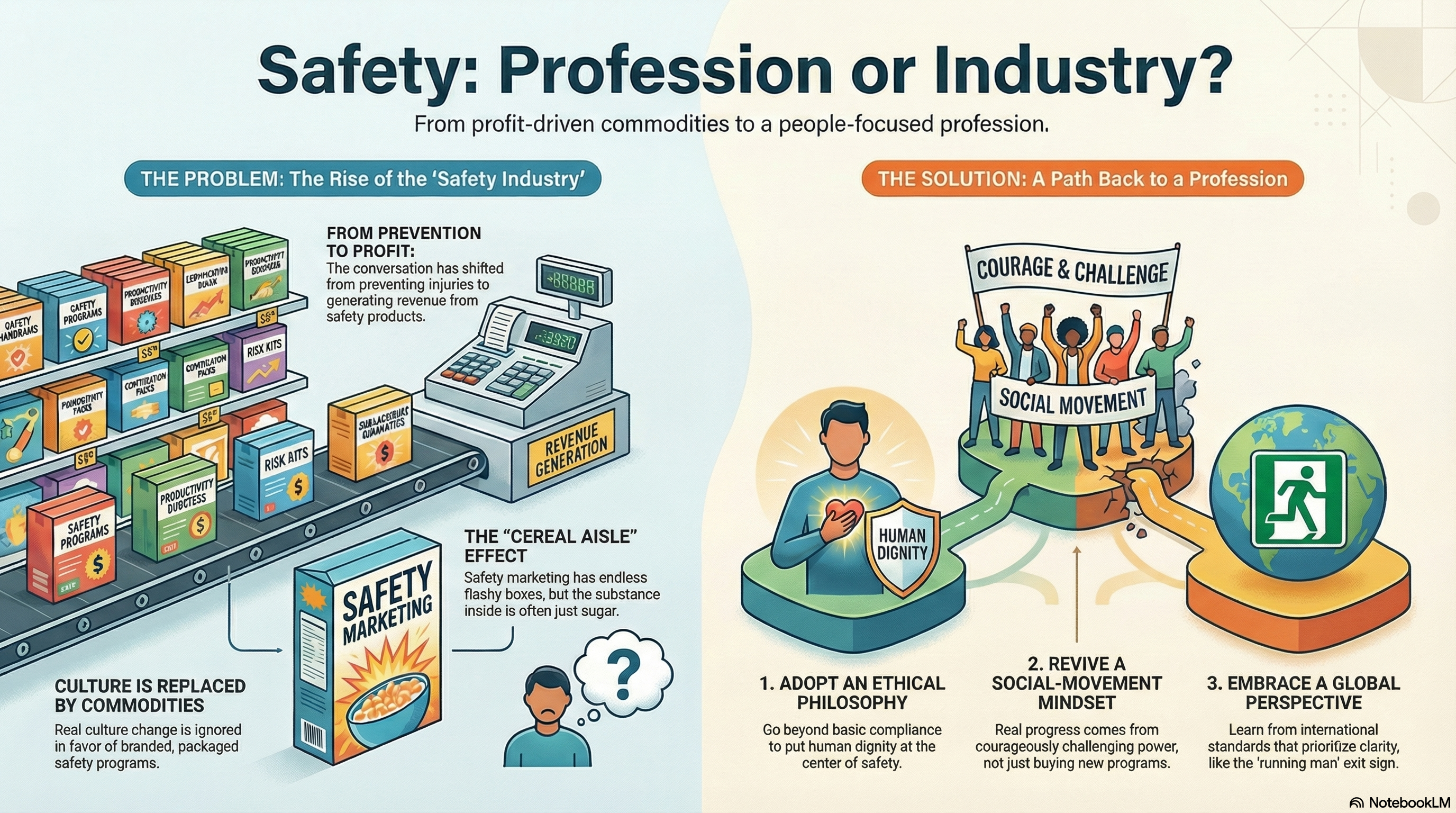

One of the major shifts in occupational safety over the last three decades is the move from a profession to an industry, and with it, the commodification of safety programs. In the 1990s, the language of safety centered on preventing injuries and illnesses; today, it often centers on how much revenue a safety program, product, or ideology can generate.

I started my career in 1994, when occupational safety was shaped heavily by insurance companies, regulators, and researchers who were exploring the concept of culture. In 1995, the emphasis in the United States was still on regulation and employer costs rather than a clearly segmented “safety industry” the way market-research firms define it now. Today, however, the broader Occupational Health & Workplace Safety Services sector in the U.S.—including consulting, training, and compliance services—is valued in the billions of dollars annually, and that financial scale influences how safety is talked about and sold.

This shift in money and marketing has changed the language of safety. Terms like leadership often function as euphemisms for authority, allowing those at the top to avoid meaningful accountability for safety outcomes. Many CEOs do not know—or do not care—how their behavior and decisions shapes the organization’s culture, and appeasing the board often takes priority over employee well-being, health, or safety. What some academics now call “psychological safety,” the Norwegian researcher Johann Galtung has described more starkly as “psychological violence,” highlighting the harm caused when people with authority dismiss, silence, or punish those without it. Galtung’s concept of indirect violence aligns with American culture, where access to basic human rights is often contingent on having employment.

Does any of this matter? It does, because commodification tends to stop at programs instead of transforming culture. Safety culture, a term popularized after major industrial disasters in the late 1980s, was initially a novel construct in the safety field. Yet organizational psychologists had been studying organizational culture since at least the 1930s. Across these disciplines, a common view is that culture—whether organizational, national, community, or family—emerges from climate: in simple terms, how people with authority treat people without authority. Under that lens, “safety culture” is not a separate category at all; it is one expression of human culture.

Parenting made this distinction between culture and programs very clear to me. As an occupational safety professional, I watched safety turn into slogans, brands, and packaged systems. None of that helped me raise two daughters. I never asked my kids to sign a form confirming they had read and understood the lawn mower’s operating manual. At home, health and safety are cultural, not programmatic—they live in daily habits, expectations, and how we treat each other, not in binders and logos.

When I think about today’s safety “industry,” the image that comes to mind is standing in the cereal aisle: endless boxes with loud claims and bright branding, but inside is just sugar. There is a lot of marketing, but not always much substance. There is also too much money at stake to expect the industry, on its own, to revert to a profession grounded in ethics, courage, and worker wellbeing. For people starting their careers now, the commercialization of safety may feel normal, even inevitable.

If this is a problem, what is the solution? For me, it starts in history. First, occupational safety needs a philosophy—a clear set of principles about people, work, and harm—that goes beyond compliance and branding. Safety becomes an ethical pursuit. Second, safety needs to recover a social-movement mindset. During the American industrial revolution, progress in safety was driven by courageous workers who spoke out against conditions in mining, railroads, and manufacturing. Safety advanced because people challenged power, not because a new program was rolled out. Third is adopting a multicultural perspective. The United States has often pursued its own standards, isolating itself from the lessons and philosophies of countries that industrialized earlier. A small but telling example is the exit sign: while much of the world adopted the green “running man” pictogram beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. largely held onto text-based, red EXIT signs and has been much slower to change. Today, the running man is only gradually appearing, with some airlines and a few other industries starting to make the shift from red to green.

To move from a safety industry back toward a safety profession, the field must reconnect with that history, place culture above commodities, and put human dignity back at the center of its work. The mechanism for this shift is a humanistic focus on wellbeing. Workplace health and safety becomes well-being, health, and safety—because where well-being leads, health and safety tend to follow.