Planetary Health and Community Well-being

State of Planetary Climate Health

The Global Climate at a Glance

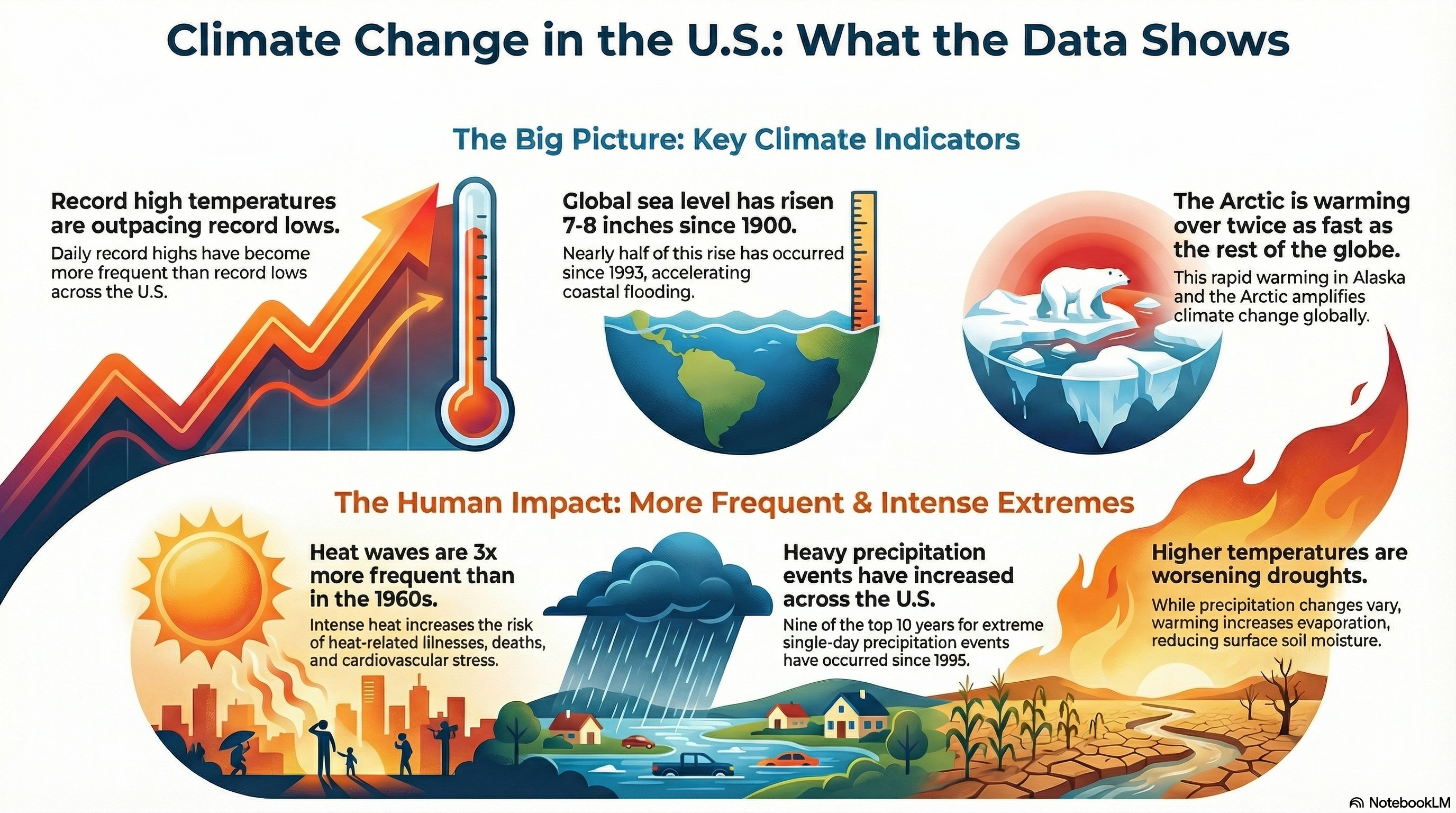

Human activities have pushed greenhouse gas concentrations, especially carbon dioxide, to levels not seen for several million years, committing the planet to long‑lasting warming, sea‑level rise, and ecosystem stress. Global average temperatures have already risen more than 1 °C above pre‑industrial levels, and the world is experiencing more frequent and intense heat waves, heavy rainfall events, droughts, and wildfires as a result.

Despite growth in renewable energy and stronger climate policies in many countries, global emissions remain high, and the remaining “carbon budget” compatible with limiting warming to safer levels is now very small, meaning rapid and sustained cuts in emissions are needed to avoid more severe impacts.

Big Emitters and the Political Landscape

China, the United States, and India are currently the three largest greenhouse gas emitters, together accounting for a very large share of global annual emissions, although their per‑person emissions and historical responsibilities differ substantially. All three participate in international climate processes and have announced emissions‑reduction targets and clean‑energy goals, but their policies and political debates often fall short of what scientific assessments indicate is needed to meet agreed temperature limits.

International climate diplomacy is under strain: negotiations frequently stall over who should cut emissions fastest, how much financial support richer countries should provide, and how to reflect equity and development needs in long‑term pathways. This tension plays out in the language of global stock takes, finance decisions, and technology‑transfer discussions, and it heavily shapes whether global climate goals can be met.

Tension Around Climate Science

Climate science itself is broadly accepted within the global process, but there is growing debate about how science is produced, interpreted, and used in negotiations. Many low‑ and middle‑income countries argue that scientific assessments and scenarios do not always capture their development priorities, local realities, or perspectives on fairness, and that this imbalance can influence which policies are treated as “scientifically necessary.”

As a result, resistance to certain scientific references in negotiation texts is often less about denying physical facts and more about contesting whose knowledge counts and how responsibility is framed. This is turning the treatment of science into a political battleground over climate justice and historical responsibility, not just a technical matter of accuracy.

Changing Weather and Emerging Hazards

Climate change is not only making extremes stronger; it is changing their patterns. Atmospheric rivers that bring a large share of rain and snow to places like the U.S. West are projected to become more frequent and, in many cases, more intense, raising the combined risks of both flooding and water‑supply disruption. In the United States, research shows that there are fewer days with tornadoes overall, but more tornadoes on those active days, which increases the likelihood of large, damaging outbreaks.

Globally, evidence indicates that the regions where tropical cyclones reach their peak intensity have shifted toward higher latitudes, exposing communities that have less experience and infrastructure designed for such storms. Traditional notions of fixed “seasons” for hazards like wildfires are breaking down as hot, dry conditions and fuel build‑up lead to more frequent and severe fires outside historical windows, including in parts of Europe and North America.

Health, Safety, and Well‑Being in the United States

Climate change is increasingly recognized in the United States as a public‑health and safety issue rather than just an environmental one. More frequent and severe heat waves raise risks of heat stroke, kidney stress, and cardiovascular problems, particularly for older adults, outdoor workers, and people without reliable cooling. Worsening air quality from wildfire smoke and ozone leads to more asthma attacks, lung irritation, and heart complications, and smoke from distant fires can now affect air quality across large parts of the country.

Extreme rainfall, hurricanes, and river flooding threaten lives directly and can also disrupt hospitals, power, roads, and water systems, jeopardizing access to emergency care and clean water. These events, along with worries about future disasters, contribute to anxiety, depression, and other mental‑health challenges, especially in communities that experience repeated losses or displacement.

Minnesota: A Local Snapshot

In Minnesota and the broader Upper Midwest, warming temperatures and ecological shifts are contributing to higher risks from ticks and mosquitoes and to more impactful weather events. Minnesota is consistently ranked as a high‑incidence Lyme disease state, with thousands of cases reported annually and a long tick season from late spring through early fall. Warmer conditions and changing habitats support the expansion and longer activity period of blacklegged ticks, which can increase exposure to Lyme and other tick‑borne illnesses.

The state also faces recurring West Nile virus risk, with human cases most summers as mosquitoes benefit from warm, wet conditions and standing water. Heavier downpours and more frequent very‑wet days raise flood risk and can damage homes, roads, and health facilities, while smoke from large fires in Canada or the western U.S. periodically degrades air quality, triggering respiratory problems even when no fires burn locally. These combined pressures affect not only physical health but also day‑to‑day well‑being, as time outdoors, sense of safety, and economic security are increasingly shaped by climate‑related hazards.

Planetary Health and Human Well‑Being

Taken together, these patterns show that planetary climate health and human well‑being are tightly linked. A hotter, more unstable climate is altering water, food, and disease systems, stressing infrastructure, and amplifying inequalities, while also challenging mental health as communities cope with uncertainty and repeated shocks.

At the same time, many of the actions needed to restore climate stability—cleaner air, safer housing, greener cities, resilient health systems, and fairer economic arrangements—can directly improve health, safety, and quality of life if pursued ambitiously and equitably. In that sense, the state of planetary climate health is not only a warning but also a roadmap for protecting and enhancing well‑being in places like the United States and Minnesota, as well as globally.

Example Text

Example Text

References American Public Health Association. (2025). Health threats surge as scientists warn of edging toward irreversible climate change impacts. https://www.apha.org/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Lyme disease case maps. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/data-research/facts-stats/lyme-disease-case-map.html

Commonwealth Fund. (2025). State scorecard on climate and health. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/

European Commission Joint Research Centre. (2025). GHG emissions of all world countries – 2025 report. Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission Joint Research Centre. (2025). Europe’s fire season is expanding: New JRC report shows. https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/

Grist. (2026, January 1). Wildfire smoke is a national crisis, and it’s worse than you think. https://grist.org/

Minnesota Department of Health. (2025). Lyme disease: Statistics and annual summary of reportable diseases. https://www.health.state.mn.us/

National Centers for Environmental Information. (2023). Billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/

National Centers for Environmental Information. (2022). Weather-related fatality and injury statistics. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.weather.gov/hazstat

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2023, January 9). 2022 U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in historical context. Climate.gov.

Scripps Institution of Oceanography. (2016, August 11). How the world passed a carbon threshold and why it matters. University of California San Diego.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2023). Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement: Synthesis report. UNFCCC Secretariat.

U.S. News & World Report. (2025, September 25). Climate change affects health: Here’s where. https://www.usnews.com/

World Resources Institute. (2023, February 2). This interactive chart shows changes in the world’s top 10 emitters. https://www.wri.org/