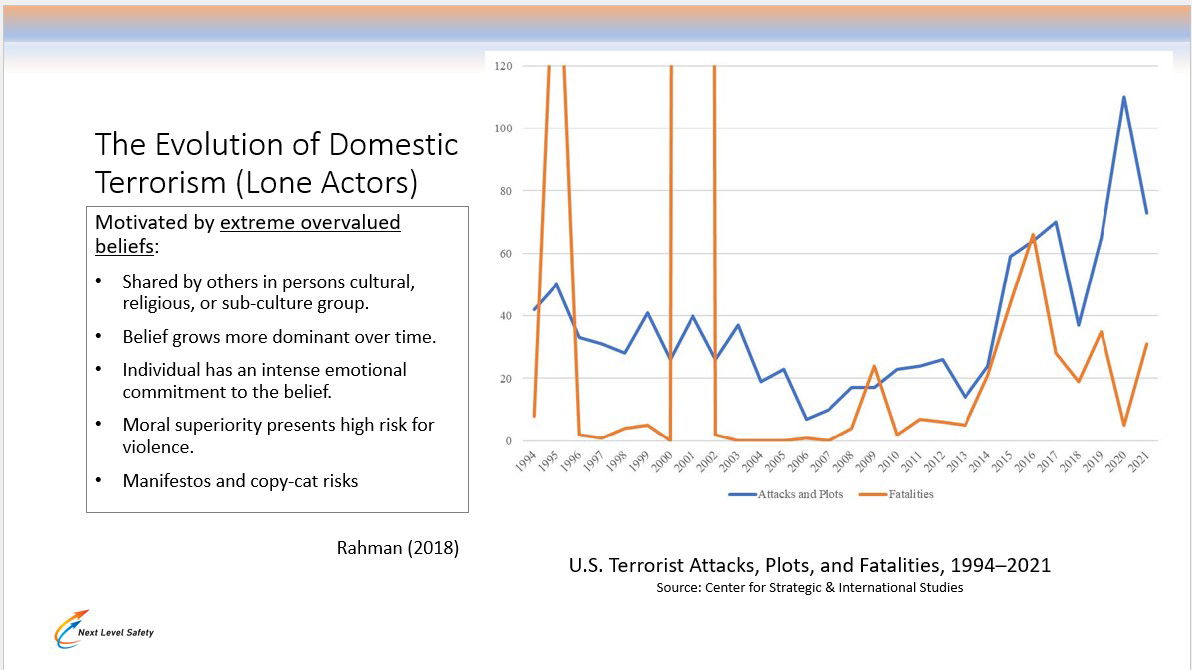

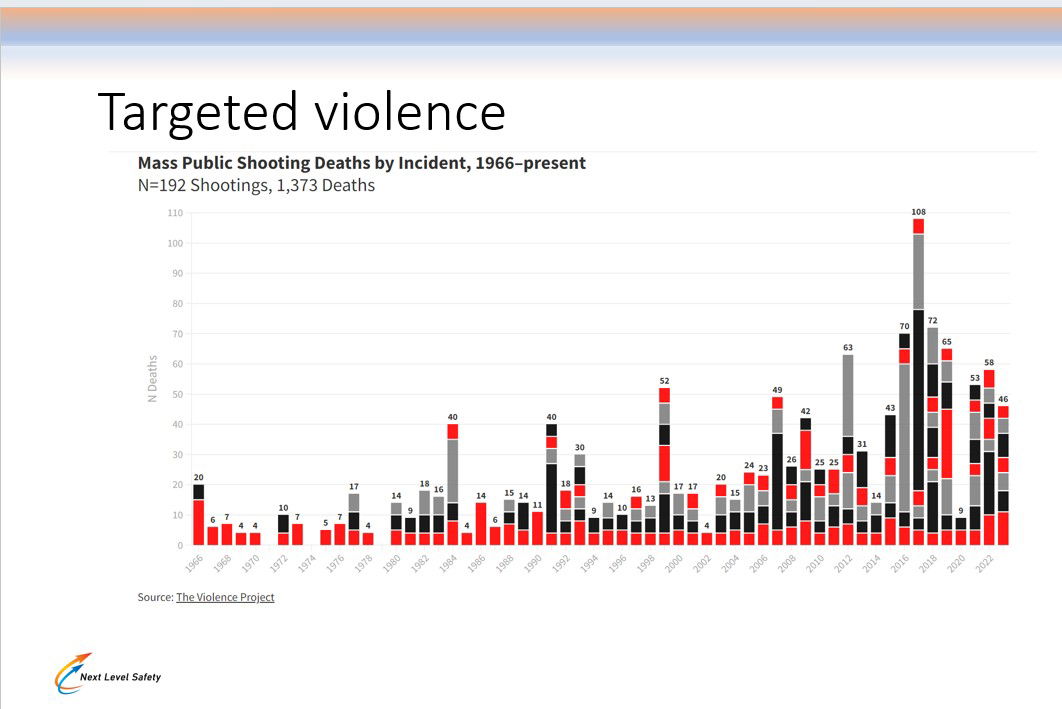

Language and definitions can be telling about a culture. The United States has a legal definition of defamation but no legal definition of hate speech and in fact, hate speech is protected under the first amendment. Are there consequences to this freedom of expression even when it results in prejudice and dehumanizing rhetoric? Recent studies are confirming what history has already taught us – that hate speech is a precursor and even predictor of violence. Before diving into the research we need a functional definition of hate speech. Although there is no unified legal definition, the United Nations states hate speech can be characterized as “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behavior, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color, descent, gender or other identity factor.” Hate speech is communication that dehumanizes an individual, group, or population. It can result in prejudice (irrational hostilities toward that group) to seeing others as less than human. Historical atrocities have this process of othering in common and was often politically motivated. Radicalization by exposure to hate speech through social media has expedited moral justification of violence revealed by the rising targeted shootings in our schools and workplaces. While targeted violence is a complex issue, a growing body of research is moving beyond anecdote and establishing the connection between what we say online and what happens offline.

1. It’s Not Just Talk. Online Hate Can Predict Offline Violence. For a long time, the argument has been made that online speech, however vile, is just talk. Research, however, now establishes a measurable, predictive link between the volume of online hate speech and the frequency of offline hate crimes. In an analysis of 532 million tweets across 100 U.S. cities, researchers at New York University found that a higher number of targeted, discriminatory tweets in a city correlated with a higher number of real-world hate crimes motivated by race, ethnicity, or national origin. Yet in a profoundly counter-intuitive twist, the same study found a negative relationship between hate crimes and online self-narrations of discrimination; in other words, online spaces where people shared their personal experiences of being targeted by hate actually correlated with fewer hate crimes. A separate study conducted with the Spanish National Police added even more surprising detail to this connection. Comparing police records of hate crimes with social media posts, researchers found that Facebook posts were a more effective predictor of violence against migrant and LGBT communities than tweets. Even more counter-intuitively, they discovered that general "toxic language" was a better predictor of these hate crimes than messages explicitly classified as "hate speech." This suggests that a pervasive culture of generalized hostility may be more corrosive and indicative of future violence than isolated, easily identifiable slurs. If online hate is a reliable predictor of offline violence, the next critical question is how this hate behaves in its own digital habitat. Does it remain static, or does it grow?

2. Hateful Echo Chambers Act Like a Virus, Spreading and Accelerating. The concept of "hate begets hate" is more than a saying; it is a measurable phenomenon in loosely moderated online environments. A temporal study of the social media platform Gab, which has been described as an alt-right echo chamber, revealed that hate speech does not merely exist on such platforms—it grows, spreads, and becomes more potent over time. This growth is often tied to real-world events; researchers noted a significant spike in hateful activity and hashtags like #Charlottesville and #UniteTheRight around the time of the white supremacist rally in August 2017, demonstrating a clear feedback loop between offline events and online radicalization. Researchers identified three key trends that demonstrate this viral effect. First, the sheer volume of hate speech on the platform steadily increased over the two-year study period. Second, and more alarmingly, new users who joined Gab later became hateful at a significantly faster rate than the platform's early adopters, suggesting a rapid and powerful process of group norm socialization. Third, the language of the entire community began to correlate more closely with the language of hateful users, indicating that the norms of the whole platform were shifting toward toxicity. The study’s authors summarized this chilling acceleration in a stark conclusion. The amount of hate speech in Gab is steadily increasing, and the new users are becoming hateful at an increased and faster rate. While this platform-level data reveals how hateful ecosystems evolve, understanding the individuals within them—particularly those who commit mass violence—requires a more granular look at their digital lives.

3. A Shooter's Social Media Isn't Always a Manifesto. It Can Be a Cry for Help or a Bid for Fame. The narrative of an online user being quietly radicalized until they explode into violence is an oversimplification. A systematic analysis of the social media habits of 44 mass shooters reveals a much more complex picture. Their online activity is rarely a straightforward manifesto; instead, it is often a public ledger of their psychological state, revealing a mix of suicidality, a desperate bid for notoriety, and the "leakage" of violent intent. This desire for fame can be an integral part of the crime itself. The perpetrator of the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting, which killed 49 people, checked his Facebook and Twitter accounts during the attack to see if his massacre was going viral. Other shooters, driven by a desire to be known, are inspired by the infamy of their predecessors. One future shooter, after seeing another attacker gain global notoriety, wrote on his blog: On an interesting note, I have noticed that so many people like him are all alone and unknown, yet when they spill a little blood, the whole world knows who they are. A man who was known by no one, is now known by everyone. His face splashed across every screen, his name across the lips of every person on the planet, all in the course of one day. Seems the more people you kill, the more your’re [sic] in the limelight. In a counter-intuitive twist, a marked absence of social media activity can also be a critical warning sign. Researchers found that some shooters stop using social media entirely in the lead-up to their crime. This sudden change in posting habits, a departure from their established baseline of online behavior, can be as telling as an explicit threat.

4. The Psychological Toll of Gun Violence Is Far Wider Than We Imagine. The psychological impact of mass shootings is like experiencing an earthquake. The victims are at the epicenter where the trauma is intense and the healing may be a long and difficult journey. The mental health consequences ripple outward, creating "co-victims" of the family members, first responders, and entire communities where an attack occurs. A 2024 national survey revealed just how wide this circle of impact is, with 20.1% of U.S. adults reporting that a mass shooting has, at some point in their lifetime, occurred in their broadly defined community. Among those who were present at a shooting but uninjured, a staggering 76.3% still reported mental health consequences. The study, however, surfaced a surprising finding when comparing the long-term psychological impacts of different types of gun violence. While mass shootings understandably cause immense and immediate distress, the data showed that survivors of non-mass shootings—such as being individually shot at or threatened with a firearm—actually reported more prolonged mental health problems. While mass shootings corresponded with greater psychological distress, the long-term impacts, including post-traumatic stress, were reported at a higher rate following non-mass shootings. Researchers suggest this difference may relate to several factors, including "differences in social support, mental health-care access, the more personal nature of non-mass shootings and exposure to ongoing unsafe environments." The focused national attention and community support following a high-profile mass shooting may not materialize for survivors of more common, less publicized acts of gun violence, leaving them to navigate a more solitary and persistent trauma

5. The Best Response to Hate Speech Might Not Be Censorship. The public debate over hate speech is often trapped in a simplistic binary of unrestricted free speech versus censorship. However, the United Nations' official strategy on the issue intervenes with a more sociologically astute framework that reframes the entire argument. The UN makes a critical legal distinction between "hate speech"—which can be harmful but isn't always prohibited—and "incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence," which is prohibited under international law. While acknowledging that hate speech can be deeply harmful, the UN's core strategy is not to silence it, but to overwhelm it. The approach prioritizes proactive measures like education, promoting tolerance, and fostering intercultural dialogue. Rather than focusing on censorship, the strategy aims to build societal resilience to hate by empowering a "new generation of digital citizens" to recognize and reject it. The core principle guiding this global strategy is one of addition, not subtraction. The UN supports more speech, not less, as the key means to address hate speech.

Community Connection The data offers a new understanding: that the predictive signal of violence isn't just overt bigotry but a broader toxic climate; that hateful ideologies don't just exist but metastasize within their digital habitats; and that the psychological wounds of violence ripple far beyond the initial blast zone, with the most common forms of gun violence leaving the longest-lasting scars. The digital and physical worlds are not separate realms. They are demonstrably interconnected, with online rhetoric acting as a leading indicator of offline harm. This evidence allows to change the narrative around gun violence while the definition of hate speech could be operationalized at the community level. It presents an opportunity to recognize the need for recognizing our own relationship with social media and promoting interpersonal connections at a community level. Ultimately, promoting productive dialogue may be better suited at a community level rather than the national level.