When most people think of Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, they picture a grim and terrifying tour of Hell. The poem’s first section, Inferno, with its nine concentric circles of torment, has so thoroughly captured the popular imagination that its imagery has become synonymous with damnation itself. We envision fire, brimstone, and grotesque punishments tailored to every imaginable sin.

Yet, to focus on the infernal machinery is to mistake the entryway for the entire cathedral. The poem's true purpose, revealed by its very title, is not to map damnation, but to chart a course for spiritual recovery. In Dante’s time, a "comedy" was not a story meant to be funny, but one that began in despair and confusion and ended in joy and enlightenment. The poem is an epic of transformation, an allegorical map of the soul’s journey out of a "dark wood" of personal crisis and toward cosmic harmony.

This 700-year-old masterpiece is far more than a historical artifact. It is a timeless exploration of human nature, morality, and the search for meaning. Our purpose here is to excavate several counter-intuitive truths about human nature and the soul's orientation toward meaning hidden within its verses.

1. It’s a "Comedy," But Not Because It's Funny

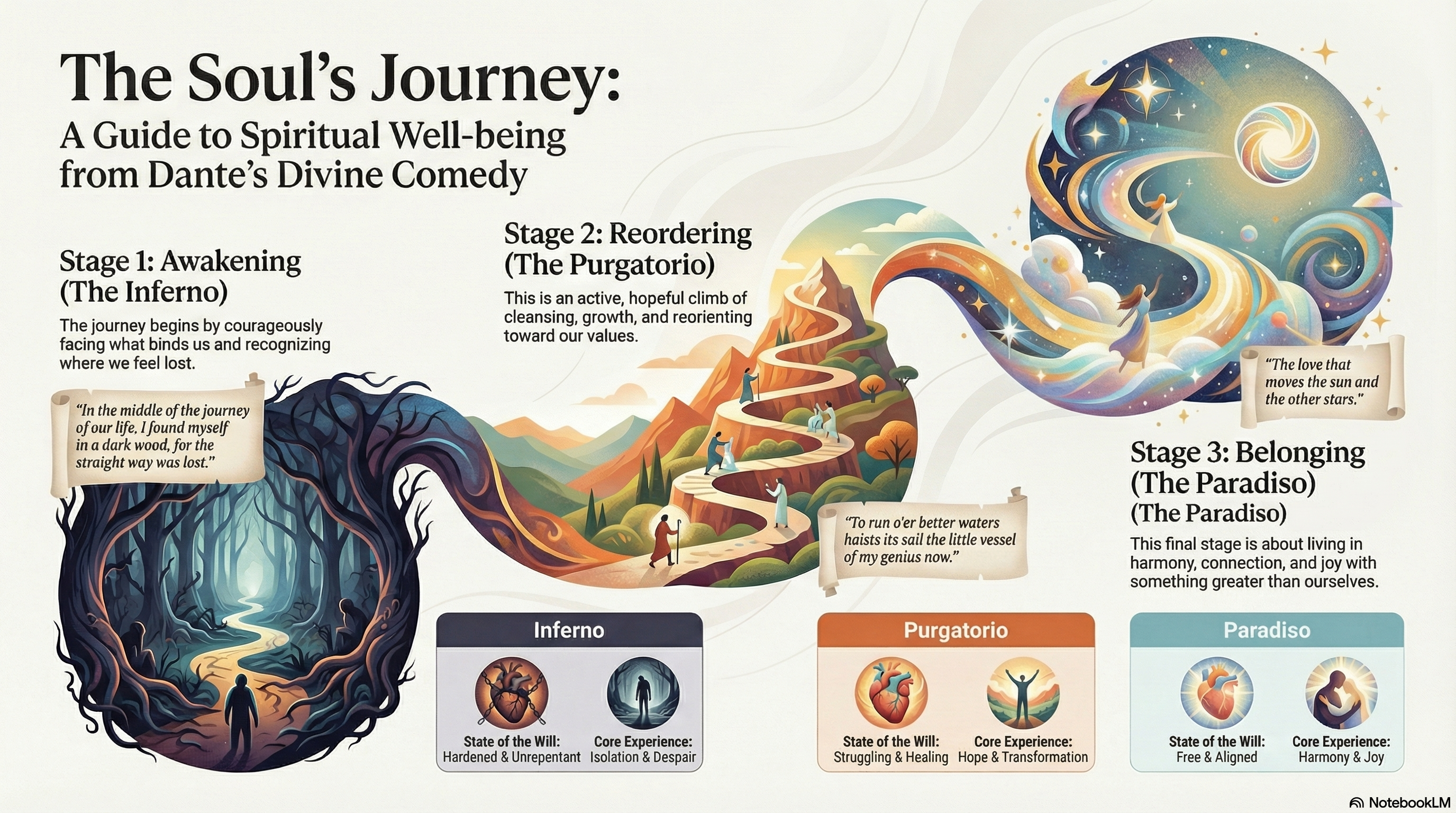

In the classical world, literary genres had specific structural definitions. A tragedy was a narrative that began in a state of happiness or order and ended in sorrow, ruin, or death. In contrast, a comedy began in a state of difficulty, chaos, or confusion but concluded with a joyful and enlightened resolution.The Divine Comedy is the quintessential example of this comedic form. Its three parts map a clear upward trajectory:

• Inferno (Hell) represents the state of despair and being lost.

• Purgatorio (Purgatory) represents the difficult process of struggle, cleansing, and transformation.

• Paradiso (Paradise) represents the achievement of joy, meaning, and union with the divine.

This reframing is philosophically powerful. It suggests that hardship and confusion are not the tragic end of a story but the necessary first act. For Dante, life’s journey is not defined by the fall from grace but by the arduous, hopeful climb toward resolution. This structure is more than a literary device; it's a theological argument that the universe itself is fundamentally comedic, bending not toward chaos, but toward justice, love, and ultimate reconciliation.

2. The Worst Sins Aren’t Violence or Lust—They’re Betrayal

Dante’s Hell is structured with a precise moral logic: the further one descends, the more severe the sin. The upper circles punish sins of "incontinence"—failures of self-control like lust, gluttony, and wrath. While serious, Dante considers these sins of passion to be less corrupting than sins of malice, which involve the deliberate use of reason to harm others.

The deepest and most terrible part of Hell is the Ninth Circle, reserved not for murderers or heretics, but for traitors. Here, there is no fire; the punishment is to be frozen in a lake of ice. The symbolism is stark: those who denied the warmth of love and trust in life are eternally deprived of it in death. At the very center of the universe, Satan himself is encased in ice, chewing on the three greatest traitors in history: Judas Iscariot (who betrayed Christ) and Brutus and Cassius (who betrayed Julius Caesar).

For Dante, this was not a theoretical sin; as a man betrayed and exiled from his beloved Florence, he understood that treason was a cold poison that dissolves the very foundations of society and self. The ultimate corruption of the human spirit is not a crime of passion but the cold, calculated decision to betray a sacred trust.

3. Damnation Isn't a Punishment, It's a Choice

A central tenet of Dante’s vision is the sanctity of free will. It is the divine gift that makes us human, allowing us to choose our path. This concept radically reshapes the idea of damnation. In Dante's Inferno, souls are not in Hell because God sent them there as retribution; they are there because they have chosen to be.

The will of the souls in Hell is described as "hardened" and "unrepentant." They are frozen in their chosen sins, eternally clinging to the pride, envy, or anger that defined them in life. Crucially, they no longer want to change. In contrast, the souls in Purgatory are defined by a will that is "struggling, wounded, but healing." They willingly undergo painful purification because their will is now oriented toward the good. This journey of the will culminates in Paradise, where the soul’s desires become so perfectly aligned with divine love that it achieves true freedom—not by losing its will, but by fulfilling it completely.

Damnation, therefore, is not an external sentence but the internal state of a soul that has permanently locked itself away from change.

"A soul that clings to its sin and rejects transformation."

4. Human Reason Can Only Take You So Far

For the first two-thirds of his journey, Dante is led by the Roman poet Virgil, a figure he deeply admires as his master and guide. In the poem's allegory, Virgil represents the pinnacle of human reason, wisdom, and classical virtue. It is reason that allows Dante to understand the nature of sin in the Inferno and the process of moral correction in the Purgatorio.

But Virgil's guidance has a limit. As a virtuous pagan who lived before Christ, he cannot enter Paradise. At the gates of Heaven, he must turn back, and a new guide appears: Beatrice. A woman Dante loved from afar in his youth, Beatrice is transfigured in the poem into a symbol of immense power.

This transition is one of the most significant moments in the work. It signifies that while human reason is essential for navigating the moral world and understanding our own failings, it is ultimately insufficient for achieving true spiritual fulfillment. To reach the highest state of joy and union with the divine, one must be guided by what Beatrice symbolizes: divine love, grace, and theological wisdom.

The Love That Moves the Stars

His final vision is not of judgment, but of a cosmic harmony that animates all of existence, resolving his journey with one of the most sublime lines ever written.

Ultimately, The Divine Comedy is far more than a medieval catalog of sins and virtues. It is a timeless map of the human condition, charting the universal movement from being lost in darkness toward finding purpose and light. Dante’s journey shows us that spiritual well-being is not the absence of hardship, but the presence of a sacred orientation—a soul aligned with its purpose.

"The Love that moves the sun and the other stars."