An Analysis of Spirituality and Modern Life

Joseph Campbell is best known for his work on ancient myths, but his real relevance today may be how clearly he saw the problems of modern life coming. Long before burnout, anxiety, and “purpose culture” became everyday topics, Campbell was asking a deeper question: What happens to people when the stories that once gave life meaning stop working?

Campbell believed that myths were never just old stories. In traditional societies, they functioned like a shared operating system. They explained how the world worked, what mattered, how to live a meaningful life, and how to face suffering and death. You didn’t have to invent meaning on your own—it was built into the culture, the rituals, and the rhythms of daily life.

Modern life, Campbell argued, quietly dismantled that shared framework.

Losing the Big Story

According to Campbell, modern societies didn’t just outgrow myth—they outpaced it. Science gave us extraordinary knowledge about how the universe works, but it didn’t replace the symbolic stories that helped people feel connected to life itself. At the same time, rapid technological change, global pluralism, and individualized identity made it impossible for any single shared myth to hold society together.

The result wasn’t freedom alone—it was fragmentation.

Myth didn’t disappear; it became personal. Each individual was suddenly responsible for figuring out who they are, what matters, and why life is worth living. That shift can be liberating, but it also leaves people unmoored. When there’s no shared symbolic grounding, people naturally look for substitutes. Political ideologies, conspiracy narratives, and extreme forms of nationalism often rush in to fill the gap. They offer identity, purpose, and a clear “us vs. them” story—but without the depth or humility of true myth.Campbell saw this not as a moral failure, but as a structural vulnerability.

Purpose vs. Being Alive

One of Campbell’s most challenging ideas is his skepticism toward the modern obsession with “finding your purpose.” He believed that chasing meaning as a goal often pulls people away from life rather than deeper into it.

We tend to treat meaning like a destination: Once I figure out my purpose, then life will make sense. Campbell thought this mindset turns life into a project instead of an experience. It keeps us mentally living in the future rather than fully present in the moment.

This is where his famous phrase “follow your bliss” is often misunderstood. He wasn’t talking about happiness, success, or self-indulgence. He was pointing to moments when the constant self-monitoring quiets down—when you’re so engaged that you forget yourself and feel fully alive. Bliss, for Campbell, was about participation, not achievement.

Seen alongside Viktor Frankl’s work, the contrast becomes clearer. Frankl showed how searching for meaning can help people survive unimaginable suffering. Campbell didn’t deny that—but he warned against turning meaning into something rigid or final. Meaning can support us, but when we cling to it too tightly, it can also become another trap. Sometimes the search itself is the point.

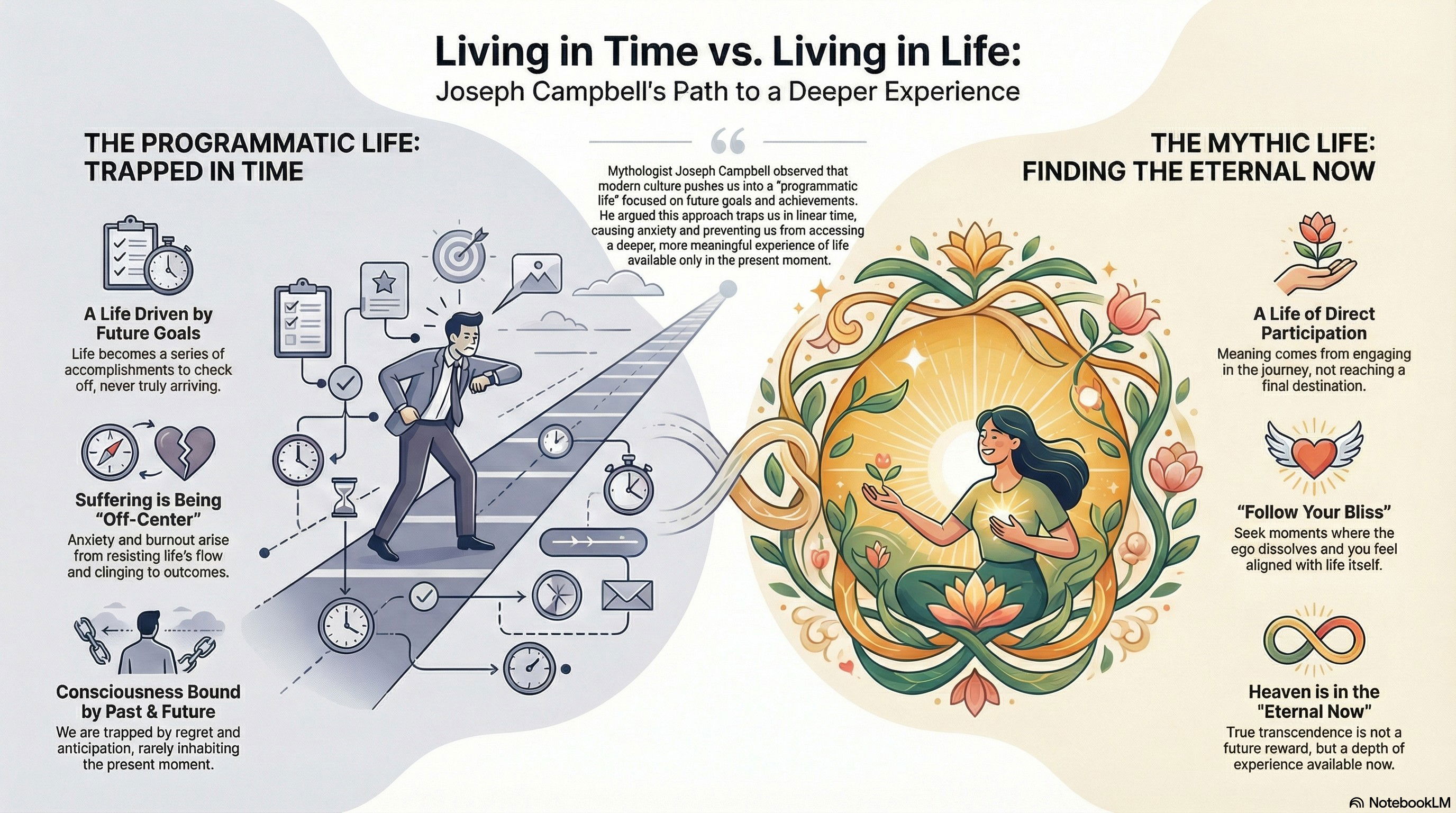

The Problem with a Goal-Driven Life

Campbell was deeply critical of what he called “programmatic living”—a way of life organized almost entirely around goals, milestones, and future rewards. Modern culture trains us to think in timelines: Once I finish this… once I get there… once I achieve that…

The problem is that “there” never really arrives.

Life becomes a constant cycle of accomplishment followed by the next target. Instead of rituals, we have résumés. Instead of presence, we have productivity. Even time itself gets treated like a resource to manage, save, or optimize.

Campbell contrasted this with what he called the “eternal now.” He didn’t mean eternity as endless time in the future, but depth in the present. When we stop obsessing over what’s next, there’s a different quality of experience available—one where life feels fuller, richer, and more real.

Rethinking Suffering

Campbell didn’t believe suffering could—or should—be eliminated. What he challenged was how much of our suffering is amplified by resistance. When we’re tightly attached to outcomes, identities, and expectations, life constantly feels like it’s going wrong.

He described this state as being “off-center.” From that perspective, suffering isn’t a failure—it’s feedback. It shows where we’re clinging instead of participating. Pain may be unavoidable, but much of modern stress comes from trying to control life rather than live it.

The Cost of Living on Hold

Campbell’s lasting insight is that many of today’s mental and emotional struggles aren’t personal shortcomings. They’re the predictable result of a culture that keeps deferring life itself. We’re always preparing, optimizing, improving—but rarely arriving.

What religions once symbolized as heaven, Campbell suggested, was never meant to be a reward at the end of life. It was a way of pointing to the depth of life when it’s fully lived.In a world obsessed with progress, his work offers a quiet but radical reminder: life doesn’t begin later. It only happens now.